How Han Kang beat older Korean writers to the Nobel

Han Kang, winner of the 2024 Nobel Prize in literature. (copyright Kim Byeong-hwan, courtesy of Changbi Publishers)

Editor’s note: In honor of novelist Han Kang recently being awarded the Nobel Prize in literature, the Hankyoreh is publishing a series of pieces in which literary experts weigh in on the significance of this award and consider what lies ahead for Korean literature.

In my view, the most important aspect of Han Kang being awarded the Nobel Prize in literature is the fact that superb translations of her work have finally allowed readers around the world to open a first page to the thick tome that is Korean literature. Without a doubt, Han is an outstanding writer, but her achievements could not exist without the rich foundation provided by Korea’s modern and contemporary literature.

There is some irony, of course, to the use of the term “rich foundation” here. This is a paradoxical literary fecundity that stems from a modern and contemporary history in which Korea has suffered more or less every sort of adversity one can in the modern world, in the forms of colonization, warfare, political division, the Cold War, military dictatorship, accelerated growth, the democratization process, and extreme neoliberalism, accompanied throughout by a stubborn patriarchal mindset.

Even if we limit ourselves to South Korean literary fiction since the peninsula’s division, we find authors both male (including Choi In-hun, Yi Chong-jun, Jo Jung-rae, Hwang Sok-yong, Kim Won-il, Hyun Ki-young, and Cho Sei-hee) and female (including Pak Kyong-ni, Park Wan-suh, and O Jeong-hui) who have battled tooth and nail against the realities of Korean society, which has simultaneously been visited by the contradictions and fetters of global history.

Their literary achievements lack nothing in comparison with those realized in the context of modern literature as produced in settings such as the English-speaking world, Europe, elsewhere in Asia, Africa, or South America. Were it not for the handicap of their work being written in Korean, it would not be at all strange to see any one of them having been mentioned numerous times as a contender for the Nobel, or to have already been honored.

The only issues have been adverse conditions existing outside of the works themselves, including the status of Korean as a minority language that has to be translated into Western ones and the fact that Korea’s dividend rate is so low in terms of the international politics of the Nobel Prize system.

But now Han Kang has finally been honored with a Nobel Prize in literature. This can be seen as the result of increases in Korea’s cultural stature and the international appeal of the Korean language, which has contributed to overcoming the issues of translation and distribution, while also enhancing its prestige and level of attention within the Nobel Committee.

It is also a case of a superlative writer, Han Kang, being present at just the right time. Her path as a candidate had been paved with previous global attention, including Man Booker International Prize and Prix Médicis honors.

But when the venerable male author Hwang Sok-yong has established a literary history far exceeding Han’s, it does raise the question of why a younger woman writer should have been the first one to receive the prize.

For many years, Hwang has been representative of the achievements and prestige of Korean fiction. Few would disagree with his being eminently qualified to become Korea’s first Nobel laureate in literature.

At the same time, he is clearly much older-fashioned than Han Kang. He is also an orthodox realist as a writer — which means that he stays true to the grammar of modern fiction. “Modern fiction” in this case involves narratives of exploration by strong, problematic male figures, such that it became known after György Lukács as a “form of mature masculinity.”

The wanderings of the protagonists in Hwang’s masterworks such as “Strange Land” or “The Road to Sampo” are actually calculated peregrinations. These are journeys one embarks on when one believes the journey to be almost at an end. While the protagonists cannot predict the future, the author is also well aware that they do not know.

More recent works by Hwang such as “The Guest” and “Mater 2-10” include elements of surrealism as the dead appear to guide the living. Even here, the fates of the figures in the form are firmly dictated by a priori truths. This is typical of modern fiction since the 19th century.

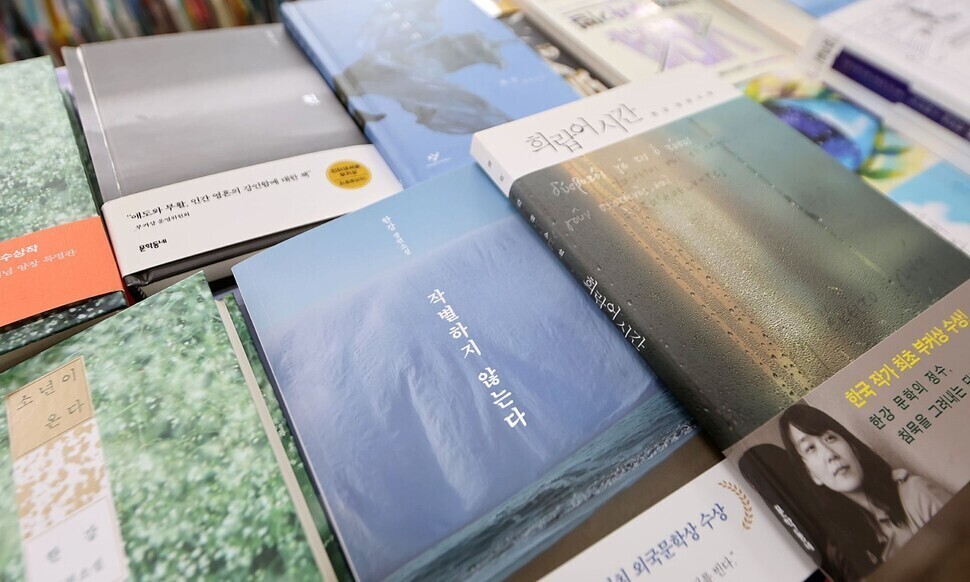

Books by Han Kang fill a display at a bookstore in Jeju on Oct. 11, 2024. (Yonhap)

Han Kang’s fiction is different. Her works are rife with questions but offer no answers. Indeed, as a writer, she guides the story in question form without knowing the answers ahead of time. This is typical of postmodern and late modern writing.

Additionally, the women who appear in Han’s fiction as speakers or characters take the form of peripheral figures, minorities, and others marginalized within the world of enlightened rationality constructed by modern men. Their words are always expressed and conveyed in ways that deviate from reason and truth.

In “The Vegetarian,” becoming a plant serves as a way for the protagonist to hold on to her sense of being as an excluded minority who is not accepted in a carnivorous world.

“Human Acts” and “We Do Not Part” are stories that ask how homo sacer figures — women and other sacrificial offerings who are stripped bare and forced into silence, unable to possess a mainstream language — can preserve themselves when confronted with the enormity of violence inflicted by the state. The elements of the surreal, esoteric, and magical that pervade her works represent both struggles and strategies of wisdom to survive the brutality of modern rationality.

The world of Han Kang’s fiction is one where the lyricism that Lukács recognized only in the context of short fiction assumes utter dominance. In that sense, it clearly deviates from the main currents of the modern novel. “The Vegetarian” and “Human Acts” unfold as series of small narratives rather than one large narrative; “We Do Not Part” is shaped primarily by the inner poetic reverberations produced through the weaving of fact and fantasy.

This represents the prose style of “immature subjects,” who cannot receive such assurances through objective truth. Within that “immaturity,” new languages, forms, and ideas emerge.

These forms predominate in Korean fiction today, and most of these works are by young women writers. This represents a resolute rejection of the male, patriarchal voices that have long dominated the world, concealed within the capital-letter subjects of nationhood, the grassroots, and class.

Somewhere along the way, this appears to have become the mainstream of Korean fiction in the 21st century. It is no coincidence that Han Kang, the recipient of the Nobel Prize, is someone born in 1970, which makes her the “eldest sister” of the women writers who represent the contemporary mainstream in Korea.

If this trend continued, Korea could well produce another Nobel laureate in literature a decade or so from now. Literature is a record not of glory but of anguish, and the same Korean society that has tormented people ironically offers the potential to nurture and reproduce these capabilities.

At root, literature exists in the forms of paradox and irony. The awarding of a Nobel Prize in literature should not be remembered as yet another “first” achieved by Korea. It should be remembered as an event proving that in all its blindness, Korean society still has the power to stop, look back, remember, and reflect in the name of literature.

By Kim Myung-in, literature critic and professor emeritus at Inha University

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Source link