Men in Contemporary Literature: Masculinity, Memes, and Modern Representations

Men Are Everywhere and Nowhere. Just a few months ago, newspapers and online magazines reported the news of a new publishing house in the United Kingdom determined to publish only men. Specifically, Conduit Books was founded by British novelist and critic Jude Cook, with the clear intent of putting themes like fatherhood, masculinity, precarious work, relationships, and “the negotiations of the 21st century as seen by a man” back at the center of narratives. According to the British author, the popularity of writers such as Sally Rooney has sparked a kind of literary renaissance that, at the same time, triggered a general disinterest in novels written by male authors, often labeled as problematic. Cook’s proposal opens several debates: how much do we need to see ourselves reflected in a text? And since when has identification been a prerogative of literature? What do contemporary men look like in literary representations?

The meme culture of the performative male

In fact, at the same time, whatever social media platform you opened in recent weeks has been filled with memes, articles, and videos about the performative male, the more accommodating and seemingly harmless counterpart of the gym bro, though by no means free from criticism. As James Factora, Staff Writer at Them, notes, the idea of a performative male seems to suggest that there exist non-performative men: but isn’t a man chronically online and a frequent user of misogynistic forums also engaging in a performance? If the former stages a farce, doesn’t that imply that the “natural” state of masculinity is being redpilled? In other words, Factora writes, these memes reinforce the idea that men entangled in the manosphere are instead some kind of standard version, and that any variation is an aberration or something to be regarded with suspicion.

Alongside projects like Conduit Books and the memes about men who read women’s works only to attract them, recent years have seen a rise in alarmist headlines denouncing a phenomenon that is, by now, quite evident: men don’t read. They don’t read as much as women, and above all, they don’t read fiction, least of all fiction written by other genders. If a man reads Sally Rooney, the subtext seems to say, it must be only to seek attention.

@tammaklily Calling such men “performative” assumes there is one authentic way to be a man, a belief rooted in misogyny and the policing of gender. Labeling that choice as performance only reinforces the conservative demand that masculinity remain fixed and oppressive. #fyp #marxist #feminism #leftist #bellhooks Juna – Clairo

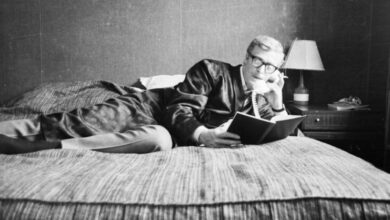

Literary representations of contemporary men

And so, one wonders, where are the literary representations of contemporary men? Some authors provide clear portrayals: Rejection by Tony Tulathimutte, recently published by E/O, tackles the sordid and embarrassing theme of romantic and sexual rejection from the perspective of different characters, one of whom is ironically similar to the performative male meme. Or Davide Coppo, who, also for E/O, published The Wrong Side, a novel in which the protagonist Ettore, a disoriented teenager searching for identity, embraces a neo-fascist upbringing. This political involvement, an inheritance of a mythologized past, shows how a certain adolescent uncertainty can take shape.

As noted by Manolo Farci, Professor of Cultural and Gender Studies at the University of Urbino, in What Remains of Men (to be published October 10 by Nottetempo), this uncertainty is also reflected in popular male role models within contemporary culture: “If more and more young women embrace emancipatory ideals and nourish themselves with feminist readings, their male peers turn to influencers inspired by a kind of caveman mystique. Professors like Jordan Peterson, who advises boys to make their bed in the morning to conquer the world, or figures like commentator Tucker Carlson, who suggests exposing one’s family jewels to red LED light to stimulate androgen hormone production, compete to see who can resurrect the most anachronistic and surreal forms of masculinity.”

Memes, masculinity, and literature as resistance

meme, as tools for spreading shared narratives, thus help reinforce the very stereotypes they try to escape. Meanwhile, the same online spaces where they are reshared become populated with “self-proclaimed gurus of masculinity who, alternating fitness tips with success-mindset tutorials, dispense worldviews that seem straight out of a poorly interpreted ethology manual” (Farci, What Remains of Men, 2025). Literature therefore appears as one of the few spaces in which to reflect on these same stereotypes, where the silent dialogue between writer and reader can give rise to new thoughts, hopefully far removed from the next Andrew Tate.