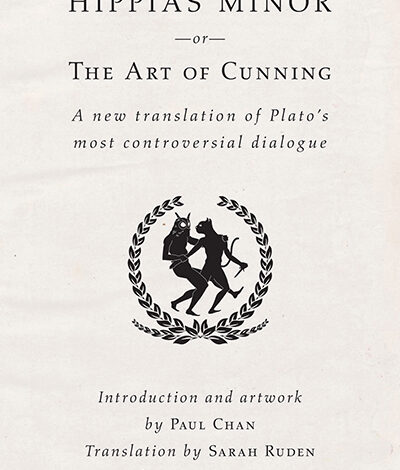

Revisiting Plato PAUL CHAN with Diego Gerard

Plato, translated by Sarah Ruden

Hippias Minor or The Art of Cunning

(Badlands Unlimited / DESTE Foundation, 2015)

Hippias Minor, one of Plato’s early dialogues, has been, if not controversial, one of his most misunderstood works. In it, Plato details a heated conversation between Socrates and Hippias, a renowned sophist polymath. The dialogue is prompted by their opposing ideas about what constitutes a “better man.” For Hippias, honesty is key. Following from this, he claims that Achilles is a better man than Odysseus—who is defined as the most cunning man of the ancient world. Socrates finds this argument bewildering. To prove that Odysseus is, in fact, the better man, Socrates sets out to define the qualities of such a man using what would seem like confounding arguments. In Plato’s depiction of the debate, Socrates contends that the better man can manipulate truth to his advantage—thus becoming better. Socrates goes even further, arguing that the man who willingly acts wrongly and unjustly is better than the man who unwillingly does so. In sum, Plato, in his portrayal of Socrates, grants cunning with virtue.

The dialogue’s controversy stems from Plato’s motives and his views on morality as expressed in other works. In Hippias Minor, Plato seems to be championing traits contradictory to his philosophy. The key concept in the dialogue is polutropos—the trait used to describe Odysseus—usually translated as “lying.” But polutropos, like many Greek words,has a range of meanings.

In 2014, Paul Chan, artist, author, and founder of Badlands Unlimited, first began exploring this “constellation of meanings,” as he calls it, in a lecture series called “Odysseus as Artist.” The lectures addressed a variety of themes, including Greek history and the relationship between art and cunning, ideas which inspired a new approach to Hippias Minor. Chan’s vision, along with work from scholar Richard Fletcher, and classicist and translator Sarah Ruden, renders a fuller, more complex reading of Plato’s classic text.

By conceiving of and translating polutropos as “cunning” (as it is also understood by poet Stephen Mitchell in his translation of the Odyssey), the content and meaning of Hippias Minor broadens the translation, allowing Plato’s argument to shine through. It’s possible to think about this translation portraying Socrates as Plato wanted him to be remembered: as the willing philosopher who, through cunning arguments, used creativity to follow reason through to its logical end.

While reframing our idea of Socrates, this new version of Hippias Minor also pays due homage to Plato. By reexamining the key concepts in this dialogue, Plato’s tone and intention gain lucidity. As the text unravels, it becomes clear that Plato is heralding the power of the creative act rather than mere deception—which may be one facet of creativity’s many elements and layers of complexity. The emphasis on the concept of cunning casts Hippias Minor in a new light, and it no longer appears contradictory to Plato’s moral philosophy.

I met with Chan this fall at the Badlands Unlimited headquarters to talk about the imprint’s new translation of Hippias Minor or The Art of Cunning.

Diego Gerard (Rail): At one point in your introduction you pose the question, “Is this Plato?” You wonder whether the voice and content you encounter in Hippias Minor are the same as those in the Republic. Was this a motivation in re-examining this text? As though wanting to find the Plato you know in this dialogue?

Paul Chan: It was one way to come to terms with how the dialogue is read and how it can be situated within the Platonic canon. Within classicism I think it’s called a developmentalist view.

Rail: “The Owl’s Legacy,” Chris Marker’s documentary film series, was one of the influences on this book. The speakers in the series repeatedly make the point that ancient Greece informs and shapes the world today. It set the parameters of modern thinking, serves as a foundation for our identities, and, as George Steiner points out in the film series, “she constantly imposes choices on us.” As you revisited Hippias Minor, did you feel that ancient Greece’s legacy had previously been misinterpreted? Is this new view on Hippias Minor an effort to shape new ideas in contemporary times?

Chan: Each generation finds new ways to interpret what came before to better grapple with what it means to be here, so to speak. It seems to me that history that is not misinterpreted, or debated, or contested, must not be that interesting of a history to begin with. As far as Hippias Minor is concerned, what I found remarkable was how it was largely regarded as a Platonic work that was more mysterious and enigmatic than illuminating and insightful. But this may have been more about how history—and Platonic scholarship in general—wants to remember Plato than anything else. If, however, one leaves behind a certain idea of what Plato is supposed to represent, then it’s possible to read Hippias Minor differently. And I think this is what we did.

Source link